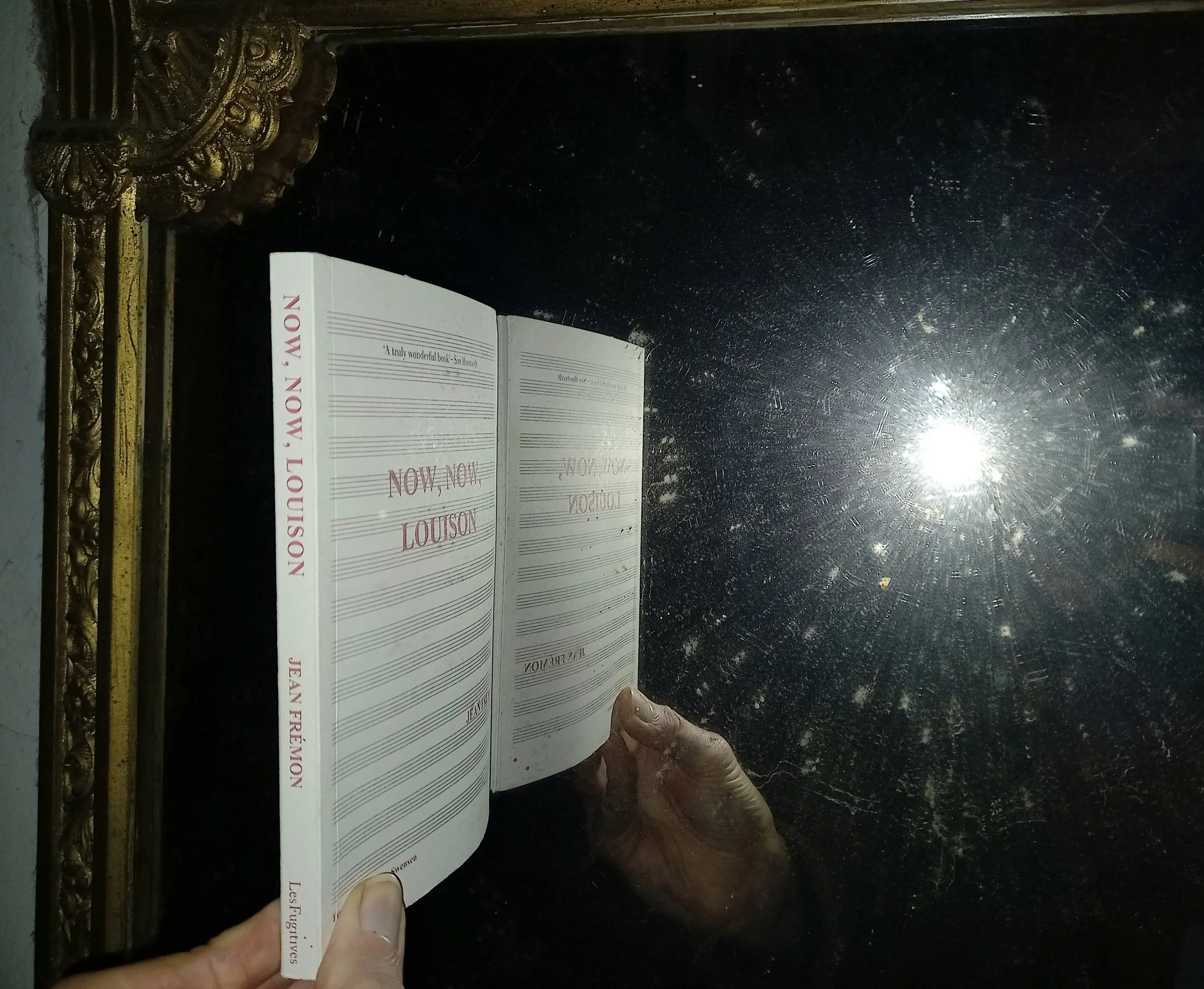

A second-person fictional autobiography, Now, Now, Louison creates its own genre. Jean Frémon — art critic, curator, novelist, poet and essayist — has painted a portrait in words of the artist Louise Bourgeois; a story of a life in memory: his memory. Frémon first met Bourgeois in the 1980s and curated both her first European show at the Galerie LeLong in Paris in 1985 and her final Parisian show decades later. He visited her in New York over 30 years until her death in 2010, saving snippets of conversation and eavesdropping on her life and work. He started this writing project in 1995, so while he states that this is from memory, and the ‘novel’ was published in French well after her death in 2016 ( and translated into English by Cole Swensen and published by Les Fugitives press in 2018), there is something of the voyeur in this telling. The narration moves from ‘you’ do this, 'you’ do that as the observer Frémon, to 'I' am, 'I' do, 'I' remember as the central character Louise. It is as if Jean Frémon has thought so intently about the artist he has moved his mind and his words into her mouth, into her head, so that the two superimpose each other. You are here, as the reader, the observer and the observed, as well as the being within the artist’s mind, the curator of your own destiny. This shouldn’t work as a device, but in fact it does, and remarkably well thanks to the prowess of Frémon's writing — subtle and exacting. The prose is like a making process — building patterns and rhythm, building a form — a sculpture chiselled out of pain, love and contradiction. It is a compelling way to tell a life, to create an understanding of a sharp and brilliant — as well as a reclusive — artist, an artist completely bound up in her own work, with an incredible sureness and, at the same time, a devastating doubt. Louise Bourgeois’s work is now well known, especially her giant spiders, her fascinating drawings, and her textile works of the body and female sexuality. In Now, Now, Louison we are given a glimpse into her life, her family and feelings of abandonment, her fraught relationship with a mother who died too young, and with a philandering father who wanted her to be someone other than who she was; her ‘escape’ to America, and the life she carved out for herself. Her ongoing art practice, mostly unnoticed during her lifetime — she was well into her 60s when the world started taking notice of her work — marks the pages in description and explanation in an emotionally charged and psychological way: Frémon does not so much describe as reflect the atmosphere of Louise Bourgious, creating, through his subtle use of language, through repetition of themes and fragments of knowledge, an essence of the woman who sculpted, painted and stitched. This is not a biography, not a work of fact. It is purposely a novel, yet Jean Frémon in this short work creates an intensely interesting portrait of an intensely interesting person. This is a book that takes the reader to a point of maybe understanding, but more importantly to a place in which to be with Loiuse, the artist, the young girl, the elusive woman and the intellectual. In the words of Siri Hustvedt, “She is here in this book, the artist I have called 'mine’ because I have taken her into my very bones, but I did not know the woman. I know her works.”

Meet Tara Selter. Antiquarian book dealer. Married to Thomas, who is also her business partner. Lives in a small town not far from Lille. Life is good. On a buying trip to Paris, the day of the 18th of November has gone pretty much to plan, with the only mishap a burn on her hand from a top of a heater. She rings Thomas in the evening, heads to bed — ice cubes against her hand — and wakes in the morning …..of the 18th of November. We meet Tara on #121 of the 18th of November. She is describing listening to Thomas in the house as he goes about his daily routine (extremely routine for her, as she has been listening to this same sequence of events for over 100 days!). Tara has decamped to the guest room — hiding from Thomas, tired of explaining to him again why she is home, unwilling to disturb his peace of mind even though he believes her — when she explains each day that time is repeating. Hiding in her own house, coming out to wash, to grab some food and get clean clothes, or even sit in the house when Thomas is out — she knows exactly when he leaves the house and the time he will return — she turns over the reasons why, the what of time, the sense that if she can only find a chink or a door (not that she believes in portals), she could find a way out of this strange situation. The day for everyone else never changes, for it has not been yet. For Tara she is caught in limbo, in some liminal space. She observes everything, intensely looking at objects, people, the night sky — looking for any changes and trying to decipher whether there is an exact time of repetition. When she was still telling Thomas they would sit together with paper, books and diagrams nutting out theories and debating philosophical explanations. (All of which would, of course, be forgotten by Thomas the next same day.) There is a wonder and a dread in her puzzling. She writes to record, to write herself into existence. “Because I am trying to remember. Because the paper remembers. And there may be healing in sentences.” As time goes by for Tara, there are inconsistencies — her hair grows, what she eats does not return to the cupboard or to the supermarket, some things stay with her, others return to their day. Why some objects stay close is a mystery. It’s fascinating to observe Tara in all her many reactions to her predicament. There is shock, then paralysis, philosophical delvings, experiments (some aimed at tricking time), rationalising, despair — the days are fog, abandonment and carefree enjoyment of being outside of time’s restraints, but mostly a desire to harness this strange beast. She contemplates herself as a monster, then maybe a ghost. She sees Thomas as a ghost, finally unreachable. Despite the times when they are intensely together, she senses the chasm that has opened between them. As the year turns, she returns to Paris to seek a resolution. We stand at the edge, waiting for Volume 2. Balle’s writing is brilliant; hypnotic. The pacing in the book changes to fit Tara’s mood, the revelations build through each sentence, through the episodic pieces, which often repeat and loop enhancing this sense of time being elusive. And like Tara, you are thinking what is this existence? Who am I in my everyday life? If I started to observe, like this woman, what would I see, sense? Is time real or a fabrication? Are we really all going along together in sync or are we each in our own world or one of the many possibilities? As you read On the Calculation of Volume 1 questions bubble away, ideas surface and you will find yourself trying to look around edges attempting to fathom the question of individual existence and the relationships we have to each other and in the wider world.

(We will discussing this interesting novel at our August book group).

Choose your edition.

“Perhaps the past is always trembling inside the present, whether or not we sense it.” Irish poet Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s debut novel is a triumph of obsession, self-reflection and love. Obsessed with the eighteenth-century poet Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, a young mother negotiates her desire to unpick the mystery of this woman as she navigates the daily tasks of her life. “I try to distract myself in my routine of sweeping, wiping, dusting, and scrubbing. I cling to all my little rituals. I hoard crusts.” Out of small spare moments, car trips to historic sites (houses, cemeteries and libraries) with her youngest child and late-night searches on her phone the shape of Eibhlín Dubh’s life is constructed or more accurately imagined. Who was she? What happened to her? Why can this woman’s life not be tracked while her father's, husband's and sons’ lives can? At the heart of the story is a poem—a lament—written by Eibhlín Dubh for her husband Art O’Leary slain by the orders of the English magistrate. “Trouncings and desolations on you, ghastly Morris of the treachery”. The poem becomes a touchstone for the narrator, a place where she can rest, where she can dream—imagine the world of this other woman who is dealing with loss, a woman who is resolute and tough, who will not lie down nor succumb to expectation from either her family nor the authorities. A Ghost in the Throat questions the telling of history—the invisibility of female voices. Scattered throughout the novel is the phrase “This is a female text”, making us aware that stories are told and histories revealed in other ways, through the body and its scars, through cloth and object, through the tasks that make us human, through the words that are sometimes unsaid and in the margins where many do not look. As the narrator discovers the poet, she frees herself along with this woman trapped in time and neglect. Ní Ghríofa writes with bewitching clarity as she describes the daily grind, with dreamlike essence in the moments of childhood memory—the longing and discovery—with realist angst about entering adulthood and motherhood, and with compelling atmosphere as the narrator unpicks the past. Rich in content and language, A Ghost in the Throat is both a scholarly endeavour and an autofiction—endlessly curious and achingly beautiful.

What happens when objects meet words and words meet objects? Back in 2008 I curated a jewellery project called LIKE. LIKE was an experiment in interpretation: a translation from object to description and back to object. I made a small object, sent it to a poet, and the poem about this three-dimensional form became the basis for nine jewellers to create their own interpretation of the original. Could the artists remake this object using only the poetic description? When the original is hidden and analysis of language is required, what will happen? How did their own making habits assist or hinder the process of creating an object where the only guidelines were a handful of words — a description that was sometimes clear, but often oblique. If the writer had been given the task of writing an instruction manual, a step-by-step guide, the resultant objects would have more alike. But this wasn’t the goal. It was a translation project, an exploration of language and communication. An exploration of both the visual and verbal. Words describe. Visual language — colour, form, scale, texture — also ‘talks’. The poet, Bill Manhire, studied the object, tried to get its measure, and described its appearance as well as its demeanour. There were clues in the poem and at times clarity of description. Yet a problem remained. The object was an alien, difficult to assimilate or easily align with something known. It was something almost familiar, but ultimately foreign. In the language of poetry it became a new thing. For the curator, the words were unexpected. The floor was open. The translation began. For what happens when we are asked to decipher what we see or what we experience? Each telling will be different. Are we more attuned today to our surroundings compared to yesterday? If we glance, what do we miss? If we study with heated concentration do we create a story that does not exist? Are our senses reliable and is our language sufficient? For LIKE, the jewellers needed to read and decipher the words of Manhire; they needed to know how to read this poem pulling from it the ‘clues’ that would be the keys to making. It wasn’t intended to trick or obfuscate, but it did prove challenging. Translation was necessary. It was surprising how various the resultant objects were, yet all expressed elements of the original. They were a family of objects related to each other. The process of translation, although flawed and sometimes deliberately sabotaged, was an experiment in interpretation that captured the essence of the original and held within its translated parts some aspects of the makers/interpreters. (The exhibition catalogue includes all 10 objects, responses from the jewellers about the process, an introduction by Augusta Szark and essay by Louise Garrett, and Bill Manhire’s poem.)

Catherine Chidgey has the ability to pull you into a wonderland before you even have a chance to blink. In The Book of Guilt you will be transported through the words and memories of Vincent to a place that feels familiar, but isn’t: to the story of three brothers who live in a grand old house with three mothers but have no sure footing at all as they travel down the staircase, touching the oak griffin on the newel post each morning for luck. But what are they wishing for? And what lucky event do they seek? It is Margate they dream of. Lawrence, William and Vincent are identical triplets. They live in a Sycamore Home. They are ‘Sycamore Boys’ — different from the children in the village. They must be protected from the illness which racks their bodies. In spite of the care of Mother Morning, Mother Afternoon and Mother Night, the boys are often unwell, and need to take medicine or have regular injections. When they are not forced to lie in their sickbeds they recite and learn from the encyclopaedic Book of Knowledge and debate philosophical conundrums in their Ethical Hour. Yet something is afoot at the home and beyond. As other boys leave for Margate, cured and well, the triplets’ frustrations grow and questions surface. When Vincent unwittingly hears he is a hero and pieces together the reasons why, the facade begins to peel away. As we venture forth through the clever three-part structure — ‘The Book of Dreams’, ‘The Book of Knowledge’, and ‘The Book of Guilt’ — we are confronted with questions about human value, authoritarian states, the willingness of a population to conform, the suspicion of the ‘other’, and the seething violence inherent in a repressed society. There are echoes of Mengele’s experiments and the science of eugenics in this alternative 1970s Britain. What seems innocent is yet another layer of wallpaper keeping the real world at bay. In this world there are other children who have questions, who are held in suspension — in a lie. Nancy, perfect in her frock and newly pierced ears, is the darling daughter of caring, over-protective parents. She’s also the girl who appears in the dreams of the triplets — to Lawrence in sweet innocence, to William as a nightmare, and to Vincent as a warning. (And Nancy has the best line — “Nothing would harm her. She was made from teeth, and she would devour the world.”) Something evil is coming. Vincent knows he must stop it, but can he? When everything you thought was true is a lie, and those you trusted are not what they seemed, you only have instinct — and that may not help at all. The Book of Guilt is captivating, full of intriguing ideas, and wonderful characters. It’s fine storytelling, and like Nancy’s teeth it will hold you even when you would rather look away. Another standout novel from Catherine Chidgey.

Han Kang's semi-autobiographical The White Book is a contemplation of life and death. It’s her meditative study of her sibling’s death at a few hours old, and how this event shapes her own history. Taking the colour white as a central component to explore this memory, she makes a list of objects that trigger responses. These include swaddling bands, salt, snow, moon, blank paper and shroud. “With each item I wrote down, a ripple of agitation ran through me. I felt I needed to write this book, and that the process of writing would be transformative, would itself transform, into something like a white ointment applied to a swelling, like a gauze laid over a wound.” Han Kang was in Warsaw - a place which is foreign to her when she undertook this project - and in being in a new place, she recalls with startling clarity the voices and happenings of her home and past. The book is a collection of quiet yet unsettling reflections on exquisitely observed moments. These capsules of text build upon each other, creating a powerful sense of pain, loss and beauty. Each moment so tranquil yet uneasy. Han Kang’s writing is sparse, delicate and nuanced. Describing her process of writing she states, “Each sentence is a leap forwards from the brink of an invisible cliff, where time’s keen edges are constantly renewed. We lift our foot from the solid ground of all our life lived thus far, and take that perilous step out into the empty air.” You can sense the narrator’s exploration and stepping out into the unknown in her descriptions of snow, in her observations as she walks streets hitherto unknown, and in her attempts to realise the view of her mother, a young woman dealing with a premature birth, and the child herself, briefly looking out at the world. Small objects become talismans of memory, a white pebble carries much more meaning than its actuality. Salt and sugar cubes each hold their own value in their crystal structure. “Those crystals had a cool beauty, their white touched with grey.” “Those squares wrapped in white paper possessed an almost unerring perfection.” In 'Salt', she cleverly reveres the substance while at the same time cursing the pain it can cause a fresh wound. The White Book is a book you handle with some reverence - its white cover makes you want to pick it up delicately. The text is interspersed with a handful of moody black and white photographs. This is a book you will read, pick up again to re-read passages, as each deserves concentration for both the writing and ideas.

Gliff is a book about authoritarianism, bonding, boundaries, bureaucracy, categories, choices, climate, community, crisis, cruelty, curiosity, data, definitions, devices, disconnection, doubt, exploitation, fables, fierceness, freedom, hope, horses, humanness, identity, imagination, kindness, language, lies, limitations, loss, meaning, meaningless, money, obedience, pollution, power, possibilities, power, profit, questions, rebellion, a red line, reduction, refugees, regulations, reports, resistance, revelation, rigidity, siblings, story-telling, a strange machine, surveillance, the digital world, the othered, the unwanted, toeing the line, truth, undesirables, verification, words.

It’s a book about now, our near future, the past, time. It’s a book that frightens, dances, plays, whispers and shouts. It’s a book that draws on mythology, fairytales, art, poetry and literature; and gives us words that have come before and will go ahead of us. It’s a warning and a promising embrace.

Siblings Briar and Rose are left to fend for themselves. Leif has found them an empty house to wait in. He’s taken their passports, left them with a stack of tinned food and a roll of notes. Their home has been red-lined, their camper van red-lined. There’s a paddock of horses waiting to be sent to the knacker’s yard. Rose and Gliff have formed an unbreakable bond of perfect trust. Briar is putting the pieces of the puzzle together, while Rose is clear-eyed in instinct if not in knowledge, in a world that insists on order. An order that feeds the machine of the wealthy and the powerful.

Ali Smith’s Gliff is a book that I didn’t want to finish. A book so interesting, nuanced and layered, that I did not want to depart. To stay in this playfulness of words, the richness of language and story, to be suspended with curiosity, while also confronted by the urgency of our 21st century landscape must surely be a work of genius. Fortunately, this book is one of a pair; —Glyph will follow Gliff.

Mesmerising from the opening lines, At Night All Blood is Black will take hold in its repetitive, rhythmic structure, creating a landscape of madness and violence that is haunting, beautiful, disturbing, and viscerally rich. This is trench warfare pared back to the lives of two Senegalese soldiers fighting for the French. Spurred on by mistaken loyalty to the mother country and by the false cultural narrative (encouraged by their Captain) of the fearsome savage — the brave, rising into no-man’s land on the shrill whistle — the attack signalled for all, both friend and foe, these two men run side-by-side screaming into the void. Alfa Ndiaye and Mademba Diop are more-than-brothers, raised in the same village, in the same family, with a shared life that binds them to each other and their destiny. The opening paragraphs of Alfa’s confession to a crime lead us quickly to the death of Mademba. In looping sequences, David Diop carves out the story through Alfa’s guilt and his jarring memories in line with the young man’s descent into madness. Guilty for denying his more-than-brother’s dying request, not once but three times, Alfa sets out to avenge his enemy as well as his conscience in an increasingly gruesome manner. An activity, at first applauded and then reviled by his brothers in arms, as well as his superiors — who eventually send him away from the front — unnerves his companions. With a brevity of action and repetitive narrative, Diop (with the excellent translation of Anna Moschovakis) invades us with the rawness, violence and fear of the front, with the absurdity of the actions of war, and the disturbing hollowing of emotion only to be replaced with superstition and mistrust. As Alfa wreaks havoc in a situation overwhelmingly chaotic, he becomes further separated from reality, and increasingly isolated, living to his own strange rationale, and becomes a symbol of bad luck, and feared by his fellow soldiers. In the second half of the book, reassigned to the Rear and a psychiatric ward, Alfa’s grip on reality tips further. Here, as his memories of village life, the disappearance of his mother, the social politics of his age sect, and the friendly rivalry, as well as enduring bond, with Mademba, come to the fore as the intensity of the Front is pushed aside, we sense why his madness descended so intensely. Here, we have myth and story. Here, we see that Alfa, without his French-speaking more-than-brother Mademba, is at sea on the battlefield and in his ability to communicate beyond gesture and drawing. Diop cleverly keeps us in Alfa’s head, our mad and unreliable narrator, but gives us enough clues to set the alarm ringing as we dip into a dream-like sequence that will take us somewhere unexpected. So unexpected that you will loop back to the start to read this slim, but unforgettable novel with fresh eyes. Stunning, unrelenting and beautifully executed.

I’m reposting my review of Delirious by Damien Wilkins this week. Delirious took out the coveted Acorn this week! If you don’t know what that is and didn’t notice the biggest event on the book industry calendar, then it’s time to take note. The Ockhams are our annual book awards, a celebration of writing and publishing in Aotearoa and home to the prestigious $65,000 Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction. Congratulations to Damien and the other award winners! Publishing in a small country is hard work, and we are lucky to have a rich and diverse literary culture. However, this can’t happen on merely good wishes, a few prizes, and ever-dwindling funding streams. Those who work in the book trade — publishers, reviewers, booksellers, authors — are highly committed, but all this doesn’t happen in a vacuum. So: celebrate in the best way by buying a book. Aotearoa authors, booksellers and publishers exist only with your support. Thank you, readers!

Review:

Mary and Pete are sorting things out. They are going to make the ‘big move’. Time to downsize, to choose low maintenance over steps one may tumble down. Mary knows Pete’s heart isn’t up to it. Pete knows Mary’s state of mind is tentative. So, no choice really. Or is there? Damien Wilkins’s Delirious is a spotlight on that thing that looms for all of us — old age. A novel on ageing and the problems this conjures, whether practical or philosophical, doesn’t sound very promising. Think again. Wilkins uses his exceptional craft as a writer, a sharp analysis of human behaviour, and an observant eye to bring us a thoughtful novel. One rich in emotion, without being cloying. In these pages are grief and loss: for Mary a phone call triggers a trauma from the past — a trauma which neither she nor Pete have fully resolved. Here is Mary, ex-cop, unsure how to proceed. Here is Pete, ex-librarian, searching for the right words. This is a novel with a heart that beats and not all the beats are the same. Take Pete’s mother. In dementia, Margaret finds an escape, of sorts. An escape from her overbearing husband and from conformity. Her mind’s slippage is both frightening and hilarious.

Mary and Pete are the every-people: people you know and maybe who you are. They are what we might call average. Mary’s a bit more aloof than Pete. Pete’s keen on helping out. The community that revolves around them, friends, family, colleagues and neighbours are all set up a little by Wilkins. Delirious takes a gentle poke at our society, and a less subtle, but delightfully funny, dig at ‘the village’. From Mary’s ex-boss perfecting his bowling, to the snide comments of the narrow-minded, to the heat-pump “we will never have one of those”, to the new but not quite right interior decor, there is something about the retirement village that doesn’t encourage the couple to unpack their boxes. What they don’t say — especially to each other — and don’t do underscores much of the novel. Then something changes. Mary and Pete will make the big move, but not the one you or they expected.

Delirious is by turns sad and funny. It’s profoundly honest about ageing and caring for others in illness, and all the dilemmas this poses, yet cleverly balances this poignancy with sly satire.

A sweet pastry with morning coffee, a biscotti for a mid-morning snack, or a satisfying panna cotta? All can be found in Letitia Clark’s Italian-inspired dessert cookbook, La Vita è Dolce. Dipping into this warm and delightful book, I was pleasantly surprised to see a wide range of baking, some simple recipes, others more complex, and some that look complicated but aren’t. That is, they look great! Almond biscuits that look like tiny perfect peaches! But Clark reassures us in her introductory paragraphs that she’s not a perfect cook, and that “cooking should never be a drama… Baking is not a divine gift or even a precise science…”, There are sections on biscotti, crostate (tart), torte, dolci al cucchiaio (sweets by spoon), gelato and gifts. Making a cake is often in celebration of a milestone event — a birthday (layer cake please!), wedding, a memorial or an achievement. Making a cake is a gift: generally you make a cake for someone in celebration or to carve out a little time. All the cakes in La Vita è Dolce look and sound delicious. Letitia Clark is a champion of the upside-down cake (as she says in her notes, her dessert recipes are Italian-inspired; she’s a French-trained Englishwoman living in Sardinia). I couldn’t go past the Candied Clementine, Fennel Seed & Polenta Cake. Those citrus and aniseed flavours, served with a good dollop of youghurt — it’s relaxed and aromatic. Need a recipe to impress and prep ahead of an occasion? The Ricotta, Pear & Hazelnut Layer Cake will be your jam! And a spiced pumpkin cake sounds just right for an autumn afternoon.

A sweet mouthful is a small luxury, an indulgence to lift your day or finish a meal. There’s something divine about a silky creamy panna cotta. Choose from Toasted Fig Leaf (yes, the leaves!), Roasted Almond or Cappuccino. Or head to the simpler Green Lemon Posset. The ‘Gifts’ section includes a delicious chocolate salami, playful and colourful marzipan fruits, and of course, classic panforte and truffles!

There’s plenty to keep you baking through wet afternoons and cool evenings here.

And this, along with Wild Figs and Fennel — a seasonal year in Clark’s Italian kitchen — are in our annual cookbook sale.

Emily St John Mandel’s SEA OF TRANQUILITY is a book to be lost in. It’s a book about time, living and loving. Superbly constructed, it stretches from 1912 to 2401; from the wildness of Vancouver to a moon colony of the future. A remittance man, Edwin St.John St.Andrew, is sent abroad. He’s completely at sea in this new world — he has no appetite for work nor connection — and makes a haphazard journey to a remote settlement on a whim. Here, he has an odd experience which leaves him shaken. He will return to England only to find himself derailed in the trenches of the First World War and later struck down by the flu pandemic. It’s 2020 and Mirella (some readers will remember her from The Glass Hotel) is searching for her friend Vincent (who has disappeared). She attends a concert by Vincent’s brother Paul and afterwards waits for him to appear, along with two music fans at the backstage door. It’s here, on the eve of our current pandemic, that she discovers that Vincent has drowned at sea. Yet it is an art video that Vincent had recorded and been used in Paul’s performance which is at the centre of the conversation for one of the music fans. The film is odd — recounting an unworldly experience in the Vancouver forest. A short clip — erratic and strangely out of place, out of time. It’s 2203 and Olive Llewellyn, author, is on a book tour of Earth. She lives on Moon Colony Two and is feeling bereft — missing her husband and daughter. It’s a gruelling schedule of talks, interviews and same-same hotel rooms; and, if this wasn’t enough, there’s a new virus on the loose. Her bestselling book, Marienbad is about a pandemic. Within its pages is a description of a strange occurrence which takes place in a railway station. When an interviewer questions her about this passage, she’s happy to talk about it, as long it is off the record. It’s 2401, and detective Gaspery-Jacques Roberts from the Night City has been hired to investigate an anomaly in time. Drawing on his experiences and the book, Marienbad, and finding connections between the aforementioned times and people, will lead him to a place where he will make a decision that may have disruptive consequences. A decision which will cause upheaval. Emily St.John Mandel is deft in her writing, keeping the threads of time and the story moving across and around themselves without losing the reader, and making the knots — the connections — at just the right time to engage and delight intellect and curiosity. Moving through time and into the future makes this novel an unlikely contender to be a book of our time, but in so many ways it is. Clever, fascinating, reflective and unsettling, it’s a tender shout-out to humanity.

Carl Shuker’s The Royal Free has been sitting with me for a while. I finished this novel in two minds. Was it just clever, but slightly irritating? Or was it brilliant and unsettling? Distance has made the novel grow fonder. Sometimes you read a novel for its absorbing plot, page-turning qualities and when you close the cover and come up for air you declare it wonderful, but give yourself a few months and it’s often hard to pinpoint the substance of the story. It was absorbing at the time. Of course, there are those novels which you circle back to, that stay with you for random reasons across years and through experience. The Royal Free is neither of these, but it is something. When I reviewed A Mistake, it was all scalpel fine cuts — a novel that would leave a scar. I reckon The Royal Free is more rash-inducing.

This is probably relevant with a six-month baby in the mix and James Ballard (our main guy) an editor at a medical journal, the latter's impetuous (rash) behaviour driven by frustration and grief, and the violence that permeates the novel, both on a personal and society level. (James Ballard may even claim that errors in texts creep into the lines and pages of the articles he edits a bit like an unwanted disease if he was pushed to!). It’s London 2011: there’s disharmony in the air, riots on the streets and a distinct collision of worlds. In The Royal Free this clash is played out through the office and the estate where James and baby Fiona live, and through the stories of other characters and their own particular circumstances. James is our guide through all this. After all, he is writing the style guide, and Shuker is playing puppet master, as novelists are want to do. If they're not in charge, who is? The editor? There are literary tricks and editorial in-jokes here, not all of which I caught, but enough to know that Shuker is playfully throwing a rule book in the air with some irony, while also respecting the word on the page, of which this writer is a master. And beyond the word play, the often hilarious and uncomfortable office dynamics (laugh and weep), there is a tender story about parenting, grief, and the unexpected consequences of violence on an individual and society at large. Here is a disintegration; a breaking down of expectation and logic. James Ballard is a quandary. What kind of parent leaves his baby alone to go for a run in the park? An action which plays on repeat in Ballard’s mind, which spirals to something increasingly problematic. Yet he is performing his tasks to the letter, caring for Fiona, and attempting to adjust to life without his wife. And yet he will reach out and touch danger. What is this impulse that compels us to be so complex? The Royal Free is, I think, brilliant and unsettling, and a little vexing. A bit like Mr Ballard!

Mary and Pete are sorting things out. They are going to make the ‘big move’. Time to downsize, to choose low maintenance over steps one may tumble down. Mary knows Pete’s heart isn’t up to it. Pete knows Mary’s state of mind is tentative. So, no choice really. Or is there? Damien Wilkins’s Delirious is a spotlight on that thing that looms for all of us — old age. A novel on ageing and the problems this conjures, whether practical or philosophical, doesn’t sound very promising. Think again. Wilkins uses his exceptional craft as a writer, a sharp analysis of human behaviour, and an observant eye to bring us a thoughtful novel. One rich in emotion, without being cloying. In these pages are grief and loss: for Mary a phone call triggers a trauma from the past — a trauma which neither she nor Pete have fully resolved. Here is Mary, ex-cop, unsure how to proceed. Here is Pete, ex-librarian, searching for the right words. This is a novel with a heart that beats and not all the beats are the same. Take Pete’s mother. In dementia, Margaret finds an escape, of sorts. An escape from her overbearing husband and from conformity. Her mind’s slippage is both frightening and hilarious.

Mary and Pete are the every-people: people you know and maybe who you are. They are what we might call average. Mary’s a bit more aloof than Pete. Pete’s keen on helping out. The community that revolves around them, friends, family, colleagues and neighbours are all set up a little by Wilkins. Delirious takes a gentle poke at our society, and a less subtle, but delightfully funny, dig at ‘the village’. From Mary’s ex-boss perfecting his bowling, to the snide comments of the narrow-minded, to the heat-pump “we will never have one of those”, to the new but not quite right interior decor, there is something about the retirement village that doesn’t encourage the couple to unpack their boxes. What they don’t say — especially to each other — and don’t do underscores much of the novel. Then something changes. Mary and Pete will make the big move, but not the one you or they expected.

Delirious is by turns sad and funny. It’s profoundly honest about ageing and caring for others in illness, and all the dilemmas this poses, yet cleverly balances this poignancy with sly satire. Up for the big prize — The Acorn* — it’s a worthy contender and in very good company. A village of books waiting for judgement day.

* The Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction will be announced May 14th at the Ockham Book Awards. Read the shortlist now!

If you haven’t come across Maira Kalman’s work, you’re in for a treat. These seemingly ‘nice’ paintings are loaded with meanings, and double meanings, with irreverence and wit. They can also be morose or mundane, profound and sorrowful; Kalman’s wry humour keeping the darkest emotions at bay. They capture the full gamut of human life and interactions. And within all these complex emotions that Kalman’s picture and text publications provoke, there is a remarkable lightness which is exhilarating, making her books the ones you want to keep close. In Still Life With Remorse: Family Stories Kalman unpicks her own and other family histories. Here are the famous, mercilessly poked at. The Tolstoys’ disfunction, Chekov’s misery, Kafka and Mahler both bilious driven by regret (and family) to create, and here is Cicero regretting everything. But these are mere interludes, along with the musical intervals, to the stories at the heart of this collection of writings and paintings. Here are the empty chairs, the tablecloths, the people gathered, the hallway, the death bed, the flowers in vases and the fruit in bowls, all triggering a memory, all resting not so quietly. Here are the parents, the uncle, the sister. Here is the aging, the forgetting and the not forgiving. Stepping back to the Holocaust, to Tel Aviv, to those that left and to those that were erased. Here are the choices and the impossible sitting around the room still living. Walking through one door and into another place, remorse following. Despite it all, there is a way to step out of one’s shoes and walk free. Still Life With Remorse is, in spite of itself, life, that is, merriment.

I was beguiled initially by the cover of this book, then the title, then the recommendation by Megan Hunter (author of The End We Start From), and after that the description. Forty women in an underground bunker with no clear understanding of their captivity. Why are they there? What was their life before? And as the years pass, what purpose do the guards, or those who employ the guards, have for them? The narrator of this story is a young woman—captured as a very young child—who knows no past: her life is the bunker. The women she lives with tolerate her but have little to do with her and hardly converse with her. She is not one of them. They have murky memories of being wives, mothers, sisters, workers. They know something catastrophic happened but can not remember what. The Child (nameless) is seen as other, not like them, not from the same place as them. The Child has been passing the days and the years in acceptance, knowing nothing else, but her burgeoning sexuality and her awareness of life beyond the cage (she starts to watch the guards, one young man in particular), limited as it is to this stark underground environment, also triggers an awakeness. She begins to think, to wonder and ask questions. As she counts the time by listening to her heartbeats and wins the trust of a woman in the group, The Child’s observations, not clouded by memories, are pure and exacting. We, as readers, are no closer to understanding the dilemma the women find themselves in, and like them are mystified by the situation. Our view is only that of The Child and what she gleans from the women—their past lives that are words that have little meaning to her, whether that is nature (a flower), culture (music) or social structures (work, relationships)—this world known as Earth is a foreign landscape to her. When the sirens go off one day, the guards abandon their positions and leave. Fortunately for the women, this happens just as they have opened the hatch for food delivery. The young woman climbs through and retrieves a set of keys that have been dropped in the panic. The women are free, but what awaits them is in many ways is another prison. Following the steps to the surface takes them to a barren plain with nothing else in sight. What is this place? Is it Earth? And where are the other people? Will they find their families or partners or other humans? The guards have disappeared within minutes—we never are given any clues to where they have gone—have they vapourised? Have they left in swift and silent aircraft? The women gather supplies, of which there are plenty, and begin to walk. I Who Have Never Known Men is a feminist dystopia in the likes of The Handmaid’s Tale or The Book of the Unnamed Midwife but is more silent, more internal, and both frustrating and compelling. I found myself completely captivated by the mystery of this place and the certainty of the young woman. The exploration of humanity and its ability to hope and love within what we would consider a bleak environment, and the magnitude of one woman to gather these women to her and cherish them as they age is exceedingly tender. The introduction by Sophie MacKintosh, which I recommend reading after rather than before, adds another layer of meaning to the novel. I Who Have Never Known Men is haunting and memorable—a philosophical treatise on what it is to be alone and to be lonely, and what freedom truly is.

Oliver Wormwood is struggling to find a Trade. His five older sisters are all amazing. One is a mage, another a lawkeeper, Willow is a ranger, another a blacksmith and the first-born an explorer. All roles his father admires. Oliver isn’t great at any of them. The Calling day is not going well, and the last option presents itself with the late arrival of the librarian. Oliver’s life is about to change. It’s not the most daring Trade. Or so he thinks…. Day one in the Library, the head librarian drops dead in mid-sentence, there are cats that appear from nowhere, and the books seem to have a life of their own! This job may not be as dull as Oliver thought! And in fact a bit more dangerous than anticipated. But can he survive the day!

There are strange comings and goings, complicated enquiries, and much to learn about the returns system, the bookworms (large and hungry) who come out at night, the bats, and the hoovering books! Luckily, Oliver isn’t completely on his own. There’s a girl called Agatha who lives in the library and knows her way around, willing to give Oliver a helping hand. Yet there’s something odd about her. One moment she’s there right beside him, and at other times nowhere to be seen. There are also the cats, all with their distinct personalities and, as Oliver finds out, usefulness. One is a great guard cat, another adept at being ferocious (handy for beasts that accidently come out of books, and a pesky firedrake!), while others are great company. Even as Oliver settles into his daily tasks, things are far from plain sailing. There are thieves sneaking through the aisles, powerful books to protect, and other books that need to be handled very carefully. In this library what it says on the cover really does count; — Death by a Thousand Papercuts, anyone?

When several murders happen in or near the library, it’s time for Oliver to put his mind to the task, and solve the mystery. But who can he trust? Is the murderer in his midst? Where does Agatha dissappear to? Who is the stranger Simeon Golightly and what is he looking for? Why are some of Oliver’s sisters popping in to see him at the library? Just being friendly, or is there something else afoot? Or has a magical creature escaped its covers and gone on the rampage?

This is a highly enjoyable, amusing tale with plenty of twists and turns, with an excellent cast of brilliant characters, both human and animal. Oliver is the best friend for anyone who has ever doubted themselves, as he discovers talents he least expected and that being yourself is a good thing. If you like a book set in a library with cats, daring escapades, and magical books, The 113th Assistant Librarian will be perfect!

A conversation about hoarding, about collecting scraps of material and balls of wool, lead me to this delightful book. (Thank you to my colleague for their recommendation.) If you are a maker you will understand the problem of, and the desire for, a wardrobe just for fabric, wool, art supplies, and other ‘useful’ materials. You will also know the beauty of changing something from an remnant into an item; — something that has a new lease of life, whether that is practical or simply to behold. If I could do one thing, and one thing only, it would be to make. Current sewing projects include recutting a vintage velvet dress (some rips, some bicycle chain grease) into a new dress, and, recently finished, a long-forgotten half-made blouse — fabric a bedsheet from the op shop. So I felt completely at home in Bound. And I devoured it with pleasure over one weekend.

This is a book about a sewing journey, and a discovery journey. It’s about the end of things and the beginning of things. All those threads that tangle, yet also weave a story about who we are, where we come from and, even possibly, needle piercing the cloth, stitching a path to somewhere new.

Maddie Ballard’s sewist diary follows her life through lockdown, through a relationship, from city to city, and from work to study, all puncutated with pattern pieces, scissors cutting and a trusty sewing machine. Each essay focuses on a garment she is making, from simple first steps — quick unpick handy—to more complex adventures and later to considered items that incorprate her Chinese heritage. These essays capture the joys and frustrations of making, the dilemmas of responsible making (ethically and environmentally), the pleasure of repurposing and zero-waste sewing, and our relationship with clothes to make us feel good, to capture who we are, and conversely to obscure us. The essays are also a candid and thoughtful exploration of personal relationships and finding one’s place in the world. The comfort of one’s clothes and its metaphorical companion of being comfortable in one’s own skin brushing up sweetly here, like a velvet nap perfectly aligned.

The book is dotted with sweet illustrations by Emma Dai’an Wright of Ballard’s sewing projects, reels of thread, and pesky clothes moths. The essays are cleverly double meaning in many cases. ‘Ease’ being a sewing term, but also in this essay’s case an easing into a new flat; ‘Soft’ the feel of merino, but also the lightness of moths’ wings; ‘Undoing’ the errors that happen in sewing and in life that need a remake. There’s ‘Cut One Pair’ and' ‘Cut One Self’. This gem of a book is published by a small press based in Birmingham, The Emma Press, focused on short prose works, poetry and children’s books. (They also published fellow Aotearoa author Nina Mingya Powles’ Tiny Moons.) Bound: A Memoir of Making and Re-Making is thoughtful, charming and a complete delight. What seems light as silk brings us the hard selvege of decisions, the needle prick of questions, and the threads that both fray and bind. Bravo Maddie Ballard and here’s to many more sewing and writing projects.

Beautiful production, beautiful concept, and beautifully executed. The sixth book in the Kōrero series is a standout. You Are Here is a journey, a journey in language, a going home, a seeking of one’s place in a physical external space, and also in one’s interior self. Where do you belong? How do you go home when time and place have been disrupted? You go home by looking towards your land, your whenua. You find your culture in language, in pattern — in mark-making both literal and metaphorical. Reading Whiti Hereaka’s text, looking into Larkin’s drawings and paintings is mesmerising. Questions are provoked and thoughts step one to the next, building connections between the words and images on the page and the concepts they embody. Here there is a conversation between cousins who share whakapapa, through their words and images. As Hereaka cleverly uses the restrictions of the Fibonacci sequence in her text, Larkin’s work also has a pattern set down. Her drawings precise on the graph paper — pen-to-paper, point-to-point — building intricate relationships in space and on the page. In her artwork you see the conversation with weaving, tāniko, whakario and tukutuku patterns. The patterns building a language of connection, moving in unison with Hereaka’s text as she spirals, doubling her words and her thoughts, as she reaches for the elusive and the sure. As anger surfaces, along with shame, passion and determination. And as the language condenses in line with the sequence’s rules, you follow the pattern out and away to the end. Open this book and find on the first page, three words. “You are here.” They sit quiet, small and a little timidly in this white space. End this book and the same three words appear. “You are here” at the centre and determined, held firmly in a Larkin drawing. But the end is no end, it is another beginning, ready for what comes next. You Are Here is also, like the other books on this series, a place where excellent book production meets the content with purpose and care. (Kudos to Lloyd Jones and Massey University Press for this excellent series.) From the subtle embossed letters on the front cover to the paper stock, it is a tactile object — a book you want to enjoy and hold. You Are Here is both intense and lyrical. It is personal and universal. It is a journey of discovery and a work of strength.

If a ghost door-to-door salesperson called at your place, what would you do? In the opening story of Matsuda Aoko’s collection, Shinzaburō tries to ignore the doorbell. It’s persistent and there’s no getting out of answering the door. They know he’s home. His attempts at turning them away are fruitless. There they are — two women dressed identically, yet with different manners. “..the younger one,...raised her head to look towards the spyhole, and said in a weak, sinuous voice, “Come now, don’t be so inhospitable! O-pen up!” If a willow tree could speak, Shinzaburō thought, this is the kind of voice…He blinked and found himself in the living room.” And so, the story carries on, with our hapless Shinzaburō finding himself unable to resist the two women and their special lanterns. His wife is none too pleased when she returns and sees how he’s been duped by the ghost women. The story is premised by a traditional folktale of love and woe, 'The Peony Lantern'. Matsuda Aoko takes these traditional ghost stories and bends them into contemporary settings with her own sense of intrigue and humour. The short stories are variously gothic and satirical in their feminist reinterpretations. In 'Smartening Up', a young woman, obsessed with her body hair, is visited by her interfering dead aunt, an aunt who has definite opinions about an ex-boyfriend, and money wasted on beauticians and clothes. Mostly though she’s concerned — the young woman is destroying the power of her hair! After a bit of a tussle, the two women settle into a discussion about the aunt’s suicide and a housewife’s lot. It’s a conversation that entwines the legend of Kiyohime and ultimately, triggers a programme of hair restoration for our young heroine. “Let’s become monsters together.” Some ghosts just want to be recognised. 'Quite A Catch' dredges up a ghost from the depths, a beautiful woman who long ago in the past was murdered finds a willing partner in Shigemi who fishes her skeleton from the lake. Haunting, it’s an observant eye on expectation and loneliness. The rakugo (a Japanese form of verbal storytelling) Tenjinyama is the inspiration for the tale 'A Fox’s Life', the story of a striking unusual woman. Brilliant, at school she excels in all her subjects and in sports, always finding a shortcut to problems, finding beautiful solutions with little effort, yet she has no desire to take her learning to the next level. At work, this was no different: everything comes easily to her, but she eschews success. She marries a kind-hearted man, stays home, has children, who grow and leave home. Something remains buried within her — a reticence to fully engage all her skills. “Throughout her life, Kuzuha had always had the feeling that she was just pretending to be a regular woman. Of course, that was the path she had selected as a shortcut, and she had never once doubted her decision had been the right one…one day…it occurred to Kazuha that maybe she really was a fox.” Each story in the collection recounts a woman’s life and her place within contemporary Japanese society with links to folktales of love, woe, revenge and mystery. Running throughout the book is another thread — a fascinating twist which draws some of these stories and characters together. It’s a thread that concerns a factory, populated by both a ghost and living human workforce, producing magical or special items which find their way into the world of the living. What these items represent is never fully articulated, but the idea of this place is intriguing and it seems to represent a bridge between the two worlds of the living and dead — each fascinated by the other.

This is a remarkable piece of writing. A memoir, a story about his parents, a family history, an island’s history, a treatise on writing, a question — the question, an exploration of death, of guilt, of shame, and of dominance and harm, but also a book of forgiveness, of wonder, hope, and most definitely, of love. Here tossed up in a looping story literary geniuses rub shoulders with brilliant physicists, and the ordinary Tasmanian, alongside the forgotten, are wheeled in and brilliantly scooped up into a telling of the everything and the particular, and it’s also immensely personal. A telling which is now, the future, and the past. A past which is 40,000 years; and just a blip— a few 1000, and also the merest moment. The bomb. This is a book which talks of war and consequence, where trauma feeds its way into the rivers of generations, where violence is erased, where memory is what we have in all its unreliability, where a truth may be found in what is unsaid or voided. As the reader, are we in the river, beside it keeping pace, or watching it flow past? Or do we find ourselves in one of its many tributaries letting the current take us, to discover we need to turn back and fight our way upstream? Or is this just the task of the writer? There is turbulence — a power working at us. But when we are midstream all is clear whether we are swimming or flying. There is calm, and humour, and an imagination that brilliantly guides us and buoys us on. Flanagan’s father was a POW in Japan. Without the bombing of Hiroshima he would have died. If he had died, the author would not exist. The bomb changed the world. H.G. Wells wrote a book because he was confused about love. A book which inspired a Hungarian Jewish scientist to have an idea about nuclear chain reaction, and then fear drove him to both embrace and reject the consequences. The wry brilliance of Chekhov filters through the pages. The love of language — of words — is delightfully explored on the page and in childhood memories, and in the author’s descriptions of his father’s reading and reciting. And here is the connection to the earth: as his mother fills bags of red soil at the side of the open road for her grey Hobart suburban plot, as Flanagan lies beneath his car by the river on a dewy night, as his great-great-grandfather labours, and his mother’s father ploughs. And here is the story of genocide, whether it is here, or over there, of violence that permeates and of lives that cannot be extinguished. Question 7 is compelling, thoughtful and almost overwhelming. It’s storytelling at its finest — powerful, beautiful and deeply moving.